I felt a flicker of buried guilt as the tool pierced my skin, knowing that tattoos are forbidden in Islam. Inspired by the feeling of ownership over my body, I got my first tattoo, of the Japanese word for beauty (my fascination with the country and culture had only grown since ESL class with Ms. I started going to a salon downtown that resembled a spaceship, where you were given an asymmetrical mullet no matter what you asked for and Depeche Mode and New Order blasted over the speakers. “I became a little more adventurous with my look.

We think you’ll find this book inspiring for your own path. And by chapter 12, she’s delivering a keynote conference talk in North Carolina entitled “Spirituality as a Radical Tool.” “A cousin of mine narrowly avoided getting killed when Sunni extremists barged into a mosque during Friday prayer and opened fire.” Her family immigrated to Canada on the grounds of religious persecution.īy chapter 10, she’s joining Unity Mosque, a prayer space created for queer Muslims.

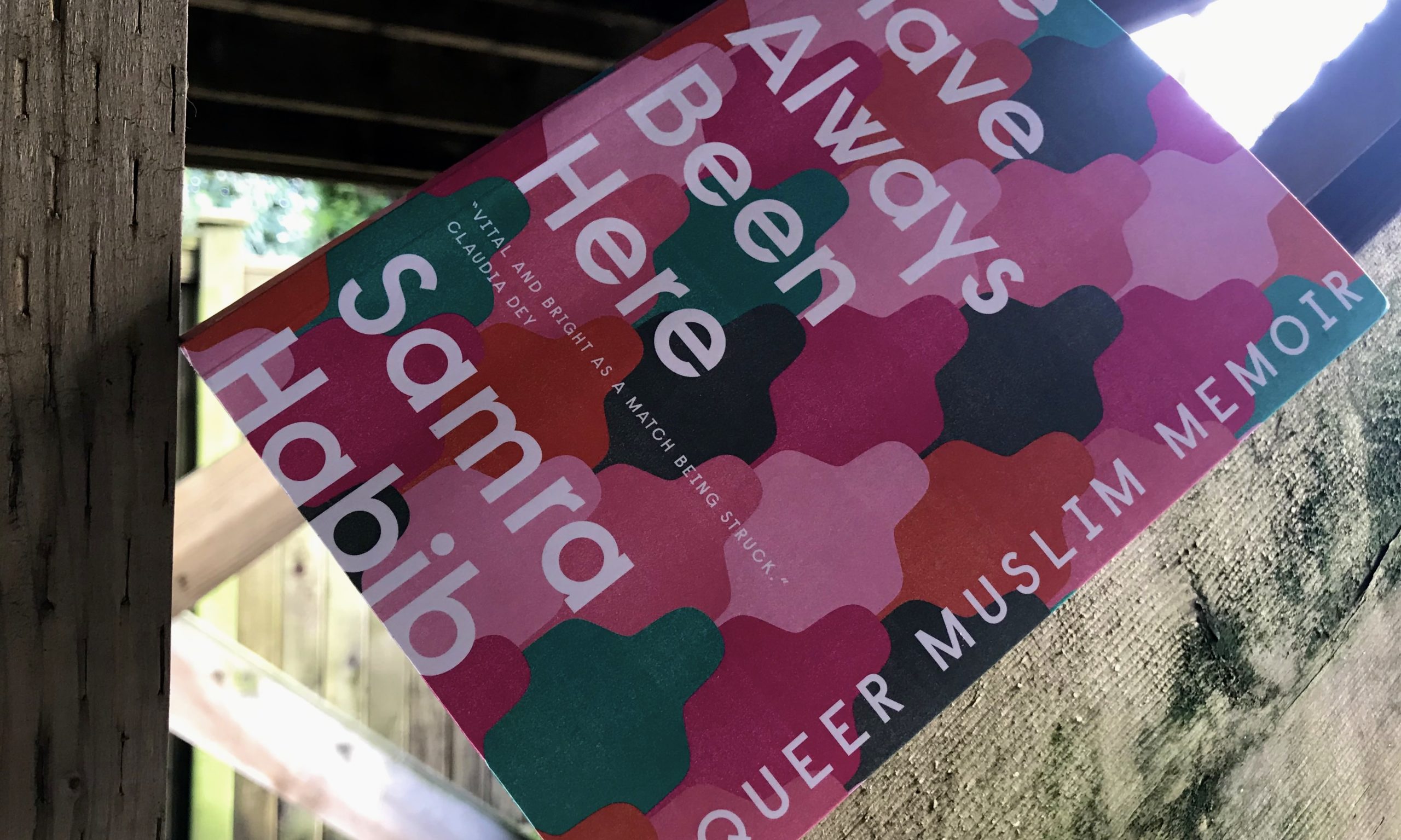

“Stories of Ahmadi businesses being set ablaze and Ahmadi mosques being besieged by gunmen are sadly common,” Habib writes. Ahmadis are routinely assaulted in Pakistan. The Ahmadiyya Movement takes its name from their founder, a Muslim reformer, who in the late nineteenth century proclaimed himself the messiah and preached non-violence and tolerance of other faiths as a way of returning to the original intentions of the Prophet Muhammad. Habib’s family was Ahmadi Muslim in Pakistan. We Have Always Been Here is also a memoir about religious difference - not only of Habib’s being Muslim in Canada, where Muslims make up only three percent of the population - but of being part of a small sect within a dominant religious tradition. She is still a young woman, and by the book’s conclusion there is the sense that she’s very much still in the process of building. After many travails and discoveries, including an arranged marriage, then a divorce, she comes out as queer and begins to build a new life. She builds it, beginning when her family arrives in Canada as refugees. This is Samra’s story of claiming her life and identity as her own. “Allah hates the loud laughter of women!” her father bellowed at her once, when she was a child playing.

It was one of the first signs that her identity was disposable.” “He had decided that Yasmin would be a more suitable and elegant name for his wife than Frida. As a child she remembers, “I’d only ever been surrounded by women who didn’t have the blueprint for claiming their lives.” Her own mother had been assigned a new name, without consultation, by her father. Samra Habib was born into a traditional Muslim family in Lahore, Pakistan.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)